Author: Rui Lobo

Part of: The College of Jesus, the College of Arts and Jesuit Architecture (coord. by Rui Lobo)

Peer-Reviewed: Yes

Published: March, 9th, 2023

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7712038

This text is a translation into English of the book chapter Rui Lobo 2012.

The latest version of this entry may be cited as follows: Lobo, Rui, “The College-University of Espírito Santo (Holy Ghost) of Évora”, Conimbricenses.org Encyclopedia, Mário Santiago de Carvalho, Simone Guidi (eds.), doi = “10.5281/zenodo.7712038”, URL = “https://www.conimbricenses.org/encyclopedia/college-university-espirito-santo-evora/”, latest revision: March, 9th, 2023.

Table of Contents

Introduction

This short text follows an in-depth study that we have completed some years ago (Lobo, 2009) dedicated to the College of Espírito Santo (or Holy Ghost) of Évora, which later became the headquarters of the local University (founded in 1559). The building was erected from 1550, and in successive construction phases, the first of which under Cardinal Henrique (1512-1580), the younger brother of King John III (1502-1521-1557). For the referred study, we carried out a set of six schematic drawings, which we now present again, and which intend to register the architectural and volumetric evolution of the complex in other six moments of its history, from its origin to the expulsion of the Jesuits, and consequent closure of the University, in 1759.

In order to substantiate the evolutionary hypotheses, we resort, above all, to the documentation collected in Rome by Fausto Sanches Martins (1994) and to the texts of the Jesuit chronicles, written in the 17th and 18th centuries. Nevertheless, for the latter sources, we should keep in mind the gap between the time of the facts and time of writing, which can be the reason for some imprecisions. This time gap is particularly noticeable in the description of the early stages of the construction process, although it is true that the later chronicles of Manuel Fialho or António Franco, from the early 18th century (and which specifically refer to the history of this college), seem to be more rigorous than the excerpts dedicated to Évora by Baltazar Teles, as part of his general work on the installation of the Society of Jesus in Portugal, during the lifetime of Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), published in 1645-47.

1554

In 1548, Cardinal Henrique sold to the Cistercian order (of which he was Abbot of Alcobaça, since 1542), for about four thousand cruzados, the college which he had been raising in the new Santa Sophia Street in Coimbra (Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Cod 8842). The King, John III, was inducing all religious orders to establish colleges beside the renewed university (transferred from Lisbon to Coimbra in 1537). The Cardinal, who was also the Archbishop of Évora (besides being the King’s brother), would not, however, give up on his original intention of creating a college for the instruction of the clergy of the Alentejo region, in southern Portugal.

In 1549, the apostolic legate, Giovanni Lipontino, passed down a brief authorizing the transfer of the incomes of the college of Coimbra to a new institute to be raised in the capital of the Alentejo. In the following year, 1550, land was acquired next to the Palace of the Castros (Paço dos Castros), future Counts of Basto, leaning against the east city wall of Évora. Soon after, the works had already started, as Baltazar Teles tells us:

For this to happen, there was a license given by the King to erect the building in Évora over a part of the city wall, which runs from the houses of the Count of Basto, until it came back over the city door, which they call Door of Machede, always going down against the northeast: over this wall fifteen cells were built on the highest floor, & on the lower floor the workshops were accommodated, with a square cloister, & a chapel [the current public ceremonies room] for saying, & hearing mass. (Teles, 1647, 317).

Coincidence or not, in October 1551, a first group of nine Jesuit priests arrived in Évora, whose arrival had been requested by the Cardinal to Simão Rodrigues, Provincial Head of the Company, for them to mission in the Alentejo (Lavajo, 1991, 35). Cardinal Henrique thought that they could be housed in his institute, together with the seminarians, so he had the number of cells of the new college expanded to thirty:

Not even after bringing the religious of the Company to Évora, did he [the Cardinal] descend from trying to have his college students with them; for that he tried to extend the building, so that everyone lived in the same place, & fitted in the same college (Teles, 1647, 317).

Another Jesuit chronicler, Manuel Fialho, describes in detail the result of this programmatic adjustment:

… Heading from the front of the church on the west side, he [the Cardinal] launched a little corridor, until it was aligned with the beginning of the first corridor; and then another that squarely connects to this first corridor. In these two corridors he ordered another 15 cubicles to be made; on the back of the church he set up a house for the library; today it serves for the disputations and other ministries; he thought those 30 cubicles were enough for what he wanted. The gap between these two little corridors, and the first, and the Church, makes almost a square, or patio, which on both sides of the southwest and northwest has the balconies supported by 11 marble columns, very well carved up to 12 palms in height: this courtyard served the College entrance that was where the door with the seal still is, on the right side [left, for those who enter] of the Church (Fialho, w/d, Tome 3, 28).

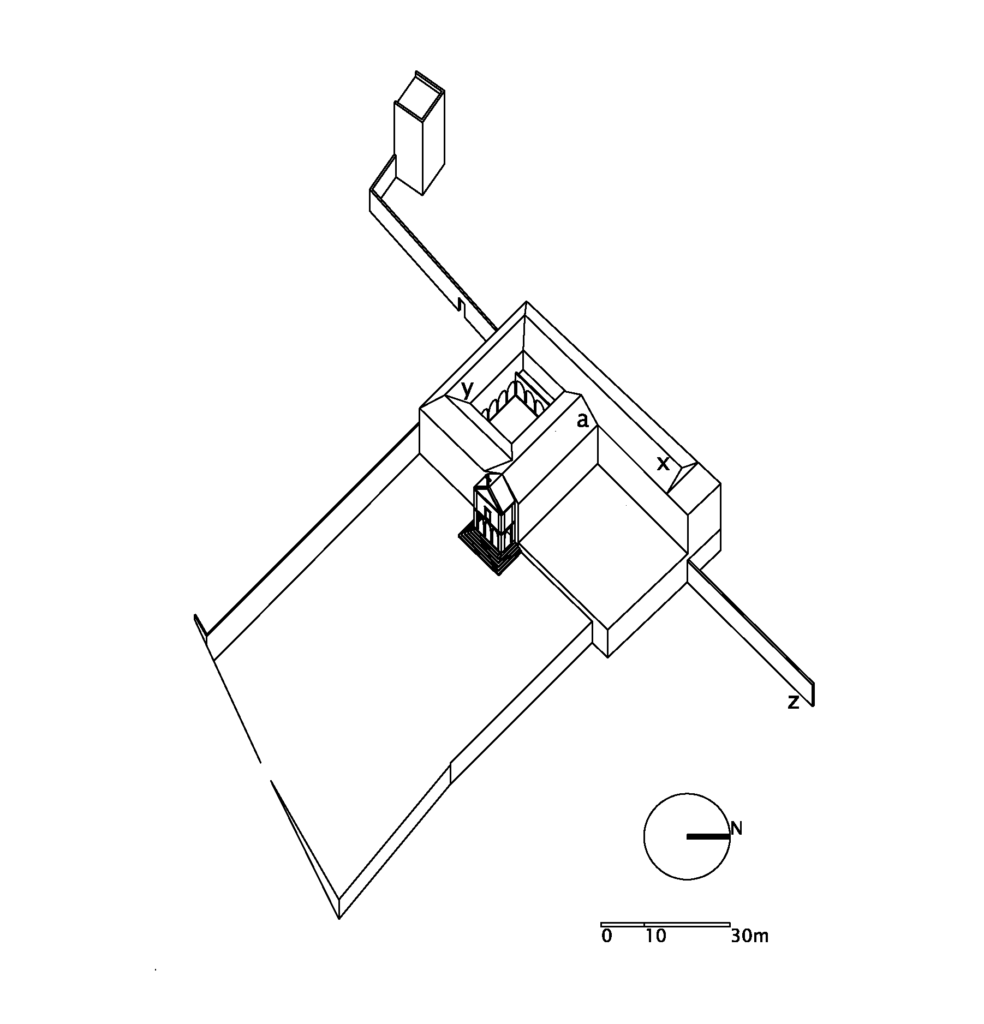

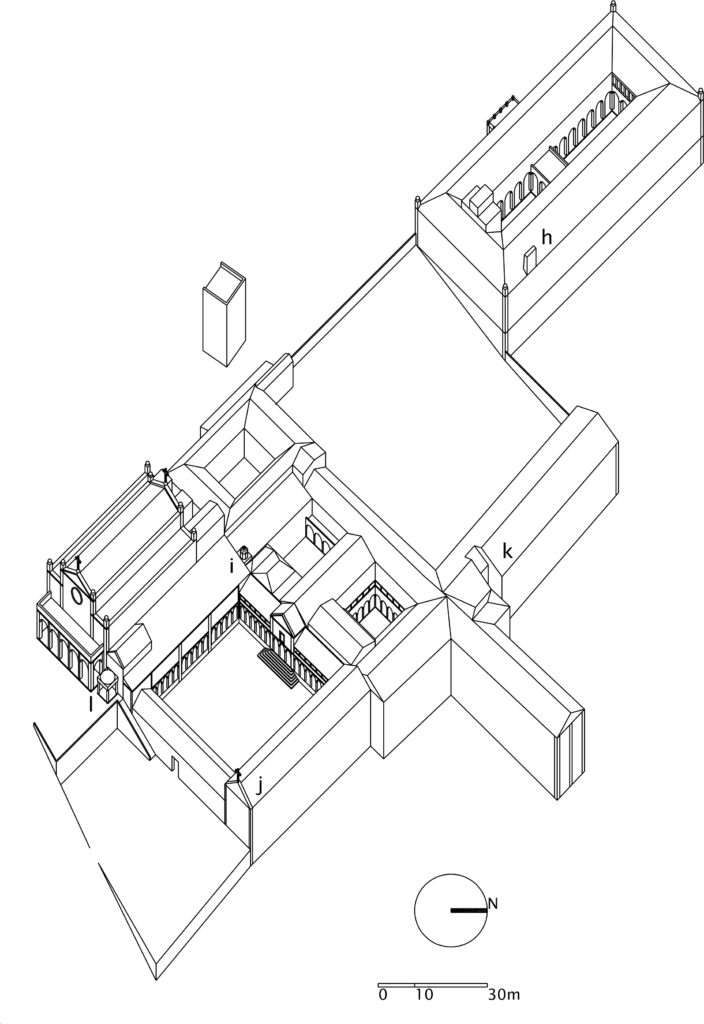

We believe this patio is the Botica (pharmacy) cloister, which today preserves only six of the aforementioned columns. This was the first patio to be built (fig.1). While this first college was being built, Luis, the Duke of Beja, brother to both Cardinal and the King, convinced Henrique to give the property entirely to the Company. It was as their exclusive tenants that the first Jesuit priests entered the college, in 1554.

Fig.1. College of Espírito Santo, conjectural reconstitution in 1554 (entry of the first Jesuit residents): a. church x. primitive wing (15 cells) y. new wings (15 cells) z. city wall.

1556

In an annual letter sent to Rome, at the end of 1556 (December 31), resident brother Francisco Morais reveals that there was

… in the middle of the courtyard a beautiful fountain, made of marble, from which flows a great deal of water. The fountain occupies the central place of a space surrounded by a magnificent portico with marble columns, making the setting most pleasant and welcoming (Martins, 1994, 211).

Although in the same document reference is made to three classrooms, two of which are still being finished, it does not appear that we are in the presence of the actual grand courtyard of the classrooms. On the contrary, the description is better suited to the cloister of the Brothers, or of the Cistern, also surrounded by marble columns, which would justify the use of the terms “pleasant” and “welcoming” to describe it (“ameno e acolhedor” in Portuguese). In this same direction seems to point out the opinion of António Franco:

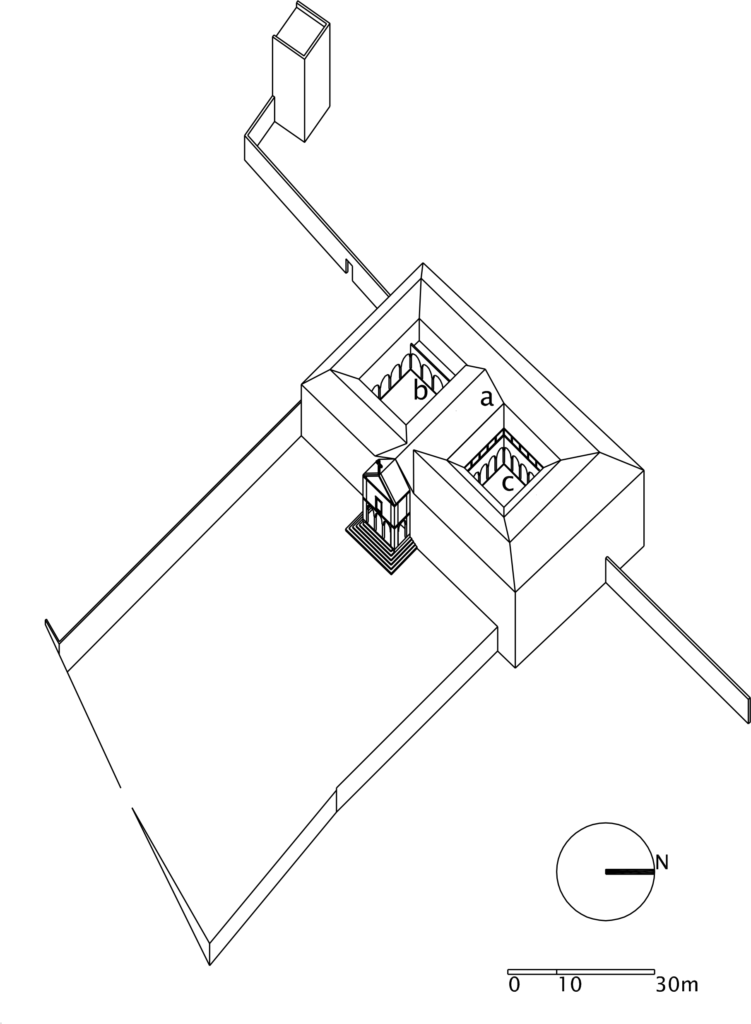

The first, or the first, part of this building, were the two cloisters of the pharmacy, & cistern, serving as Church what today is the University Hall (Franco, 1714, 2).

This is the building that a second reconstitution drawing (fig.2) intends to represent

Fig.2. College of Espírito Santo, conjectural reconstitution in 1556 (conclusion of the cloister of the brothers): a. church b. botica cloister c. cloister of the brothers or cistern cloister.

1561

In 1556, the Arts course began at the College of Espírito Santo, read by Father Inácio Martins (Franco, 1728/1945, 230). In July of the following year, John III died in Lisbon. Thus, the Cardinal was able to advance without constraints towards the creation of a new university, centered in the theological studies, a project he had been nurturing for some time. On September 20, 1558, Paul IV signed the bull that established the new University of Évora, inaugurated solemnly on 1st November 1559, although without the presence of Cardinal Henrique, withheld by the kingdom’s business in Lisbon.

Apparently, it was in that same year, 1559, that a fundamental part of the complex was advanced, the great classroom patio, or Gerais patio. It accommodated two classes of Theology and several for the preparatory course of the Arts. The works would have started as early as April, because by that time “one had already started to put hands on the matter” (Martins, 1994, 214). On 12th September of the following year (1560) it is said that

The material works are very far ahead and the body of the patio outside is almost finished: and five or six classes are being completed so one can read in them at the beginning of the year (Martins, 1994, 219).

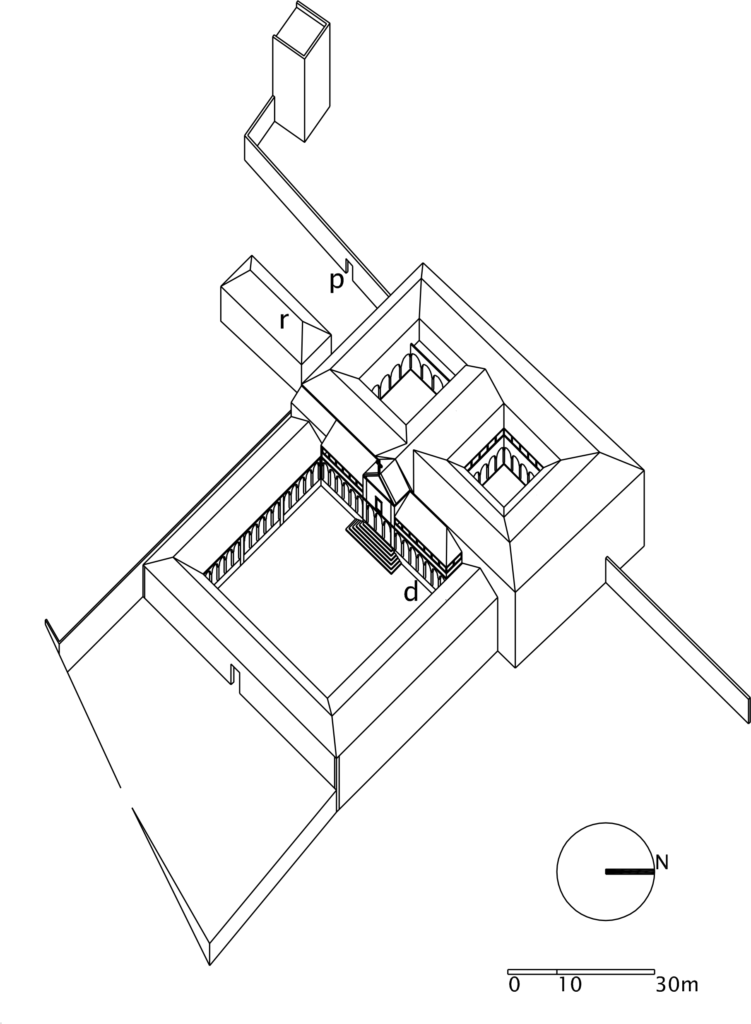

And in September 1561 the patio would be practically finished (fig.3), as Father Manuel Góis tells us:

The outdoor patio contains twelve classrooms in addition to the room that serves as a public library and another room that is used as the doorman’s house (Martins, 1994, 220).

Fig.3. College of Espírito Santo, conjectural reconstitution in 1561 (conclusion of the Gerais patio): d. Gerais patio (1559-1561) p. porta da traição (city door) r. first lodgings of the Cardinal.

The large square courtyard, 36 meters wide, was located before the complex’s primitive church (the current public ceremonies room, as we have already mentioned) and was surrounded by columns and galleries which gave access to the classrooms on all sides except for one, the entrance southeast wing. Hence, the school gate was placed opposite to the primitive church’s façade. On each side of the latter, two verandas with columns were built over the galleries, from where the Cardinal could see the students drinking from the fountain, placed in the center of the patio (Fialho, w/d, Tome 3, 72vº).

1580

After the classroom courtyard was concluded, progress was made in another sector of the current complex, in a facility more directly related to the immediate needs of the Jesuits. We speak of the novitiate, the construction of which began in 1564 (Franco, 1714, 5) under Cardinal Henrique’s distant surveillance, since he was still residing in Lisbon. A two-story quadrangular building was built, attached to the southwestern side of the College, arranged around a small patio. In 1568 it would be almost ready:

In the material of this college, a great augment happened because the new work that extends the old college is coming to an end (…) we serve ourselves from all the upper level which has a chapel in which mass can already be said, and twenty cubicles, and below there are 24 (Martins, 1994, 226).

The novitiate was still being finished while another enterprise started gaining momentum: the construction of the new church of Espírito Santo. In effect, the erection of the classroom courtyard had made the original Jesuit church inaccessible to the female public. And it was the ladies of the city who asked for the resolution of the problem:

Soon he [the Cardinal] resolved to make another Church; & as in everything he was so great, he determined to make it such, that it seemed worthy of whoever did it, & of the Lord to whom he was doing it: & so we are told, that his first intentions were to build a temple, to be equal in greatness to the Church of the monastery of the Fathers of San Francisco of the city of Évora, which is a very sumptuous work, & therefore very similar to its magnificent founder, who was the most happy King Dom Manoel, father of the Serene Cardinal. Our Fathers dissuaded him from such great thoughts (…) (Teles, 1647, 366)

The work undertaken, eventually more restrained in scale, went along quickly. The new church, begun in 1566, was already concluded in 1574, the year in which it was opened for worship, during Easter, in a ceremony that the Cardinal did not miss. The church of Espírito Santo, a project we can attribute to Afonso Álvares, constituted, together with that of São Roque of Lisbon (of the same architect), the embodiment of a national model of Jesuit church (single nave, shallow chancel, intercommunicating lateral chapels with tribunes on top, overlooking the nave) prior to the definition of the Company’s international church model, established at Il Gesù in Rome, started in 1568.

In 1570, while the new church was being erected, Cardinal Henrique was able to visit Coimbra and the works of the College of Jesus and of the attached College of Arts, which impressed him vividly:

& since, on the one hand, he greatly praised the magnificent King, his [already deceased] brother, for doing a work so royal, & so worthy of his great spirit; on the other hand, he was very disconsolate, when he remembered the building he had built in Évora, in view of what was being built in Coimbra. He soon decided to add the works of his own College, so that they could compete with those of Coimbra (Teles, 1647, 352).

It was only in 1575, with the church finished, that the desired expansion of the college could take place:

This great work ran with such fervor, that by October 1578 it was all woodened, & covered with tile in the form, in which it would stay (Franco, 1714, p.5).

Thus, on the 9th of April of the following year (1579) eight cubicles were finished in the corridor of a new pavilion launched against the northeast, inside which we are informed that “soon a good refectory with its kitchen will also be finished” (Martins, 1994, 244). It was evidently the still standing refectory of the college, located under that corridor and cells.

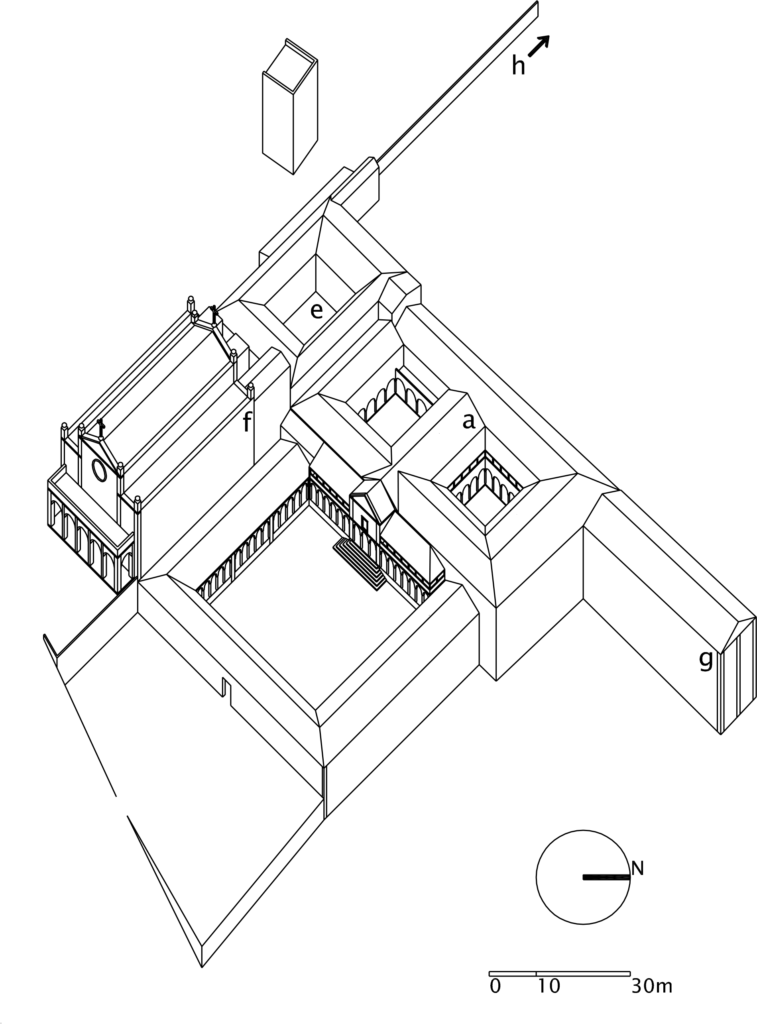

We give account of these additions – novitiate, new church and refectory block – in a new scheme of the evolution of the complex (fig.4), corresponding to 1580, the year of the founder’s death. To the northwest, the new College of the Purification (started in 1577), the “Benjamin of the Cardinal King” (Fonseca, 1728, 422) was already under construction, the sole survivor of the failed project of associating four new colleges with the central university college, idealized at least since 1573 (Rodrigues, 1938, Volume 2, Vol. 1, 85-89). On the other hand, the College of the Purification, the current seminary, also resumed the idea of an establishment for the training of future archbishopric priests, which had been (after all) at the origin of the College of Espírito Santo itself, in the already distant years of 1549-50.

Fig.4. College of Espírito Santo, conjectural reconstitution in 1580 (death of Cardinal Henrique): a. public ceremonies room e. noviciate (1564-1568) f. church of Espírito Santo (1567-1574) g. refectory wing (1575-1578) h. College of Purification (in construction since 1577).

1669

With the death of Cardinal Henrique, the Jesuits continued to expand their college-university. The attention of the priests turned once again to the Gerais courtyard. In 1591, the new entrance was completed, adjacent to the church (Martins, 1994, 247), and also a new wing, in its sequence, over the southwest gallery of the courtyard. This allowed direct access to the Jesuit community area, in order to avoid traversing the quadrangle of the classes. At the end of 1595 the dormitory on the upper floor of the opposite wing, to the northeast, was already advanced (Martins, 1994, 253-256, 745). This was the courtyard that Baltazar Teles was able to contemplate and describe in the mid-17th century:

Stands this large pateo so fancy to the eye, so graceful in its architecture, so majestic in the strength of the work, that it can make envy to the best & most royal works in all of Spain (Teles, 1647, 356).

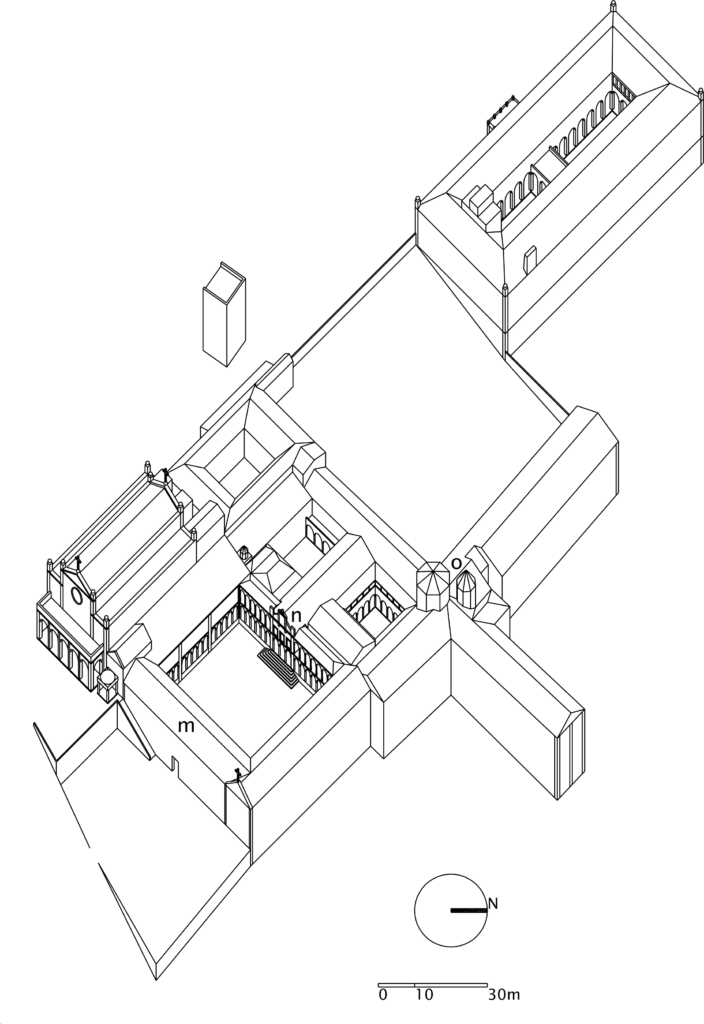

A new construction site would advance from 1641, in the back area of the college, with the start of the infirmary wing, perpendicular to the refectory wing. In this way, the cross plan scheme of this specific sector of the Jesuit complex gained substance, which can be seen in the foreground of the view of the City of Évora, drawn in 1669 by Pier Maria Baldi (Sanchez Rivero, undated), the year in which we set a new stage evolution of the ensemble (fig.5). Before (in 1666), and on the main façade, the new porch of the gatehouse had appeared (Martins, 1994, 266), a typical structure of Portuguese Jesuit colleges.

Fig.5. College of Espírito Santo, conjectural reconstitution in 1669 h. College of Purification (1577-1605): i. porter’s wing (concluded 1591) j. dormitory of the Gerais (concluded 1596) k. infirmary wing (1649-1655) l. porter’s porch (1666).

1759

Finally, let us take notice of the new interventions that took place at the end of the 1600’s and beginning of the 1700’s. In 1670-1684, the internal space of the primitive college church, which had been converted into the university ceremonies room, was remodeled:

It is in front on the door of the pateo and (almost) in the middle of the façade; and that is why it provides a lot of beauty to all the pateo (Fialho, s/d, Tomo 3º, 73vº).

The original ceiling, that no longer exists, was described by Manuel Fialho as the “Sky of Heaven”. Between 1709 and 1718 (Martins, 1994, 280-288) the front of the ceremonies room was also reformulated, giving it the more civilian air with which presides to the large patio today. The columns and arches on the upper floor, on each side of the renovated front, are also the result of this intervention. Before, around 1687 (Fialho, s/d, tome 3rd, 69vº), the upper floor had also been built over the entrance wing of the university. Finally, and on this same side, the fourth gallery was built around the patio (which became shorter), with a superimposed gallery on the upper floor.

In the center of the courtyard, the old fountain, from the Cardinal’s time, was replaced by a new piece. The renovation of the school grounds was completed between 1734 and 1740, with the remodeling of the classrooms (new doors, chairs and wooden benches, tile paneling – Martins, 1994, 293-294) that gave them the appearance they keep today. Another emblematic work, in the community area, was the dome over the crossing of the two large corridors of the dormitory and the infirmary (fig.6). “The octogonal house in the middle of the College was made by Father António Franco, at his expense, in 1726”, in the words of António Franco himself (Franco, 1728/1945, 257).

Fig.6. College of Espírito Santo, conjectural reconstitution in 1759 (closing of the university): m. new entrance wing (c. 1687) n. new façade of the public ceremonies room (concluded 1718) o. dome of the “crossing” (1726).

Conclusion

Some conclusions are possible to be reached, based on the systematization of data (from various sources and from various authors) gathered in this study. From the outset, it seems possible to confirm the particular direction that Cardinal Henrique gave to the project, during various phases and from very early on, as a result of his personal plan of creating a university-level establishment, centered on theological and also philosophical studies (the preparatory arts course).

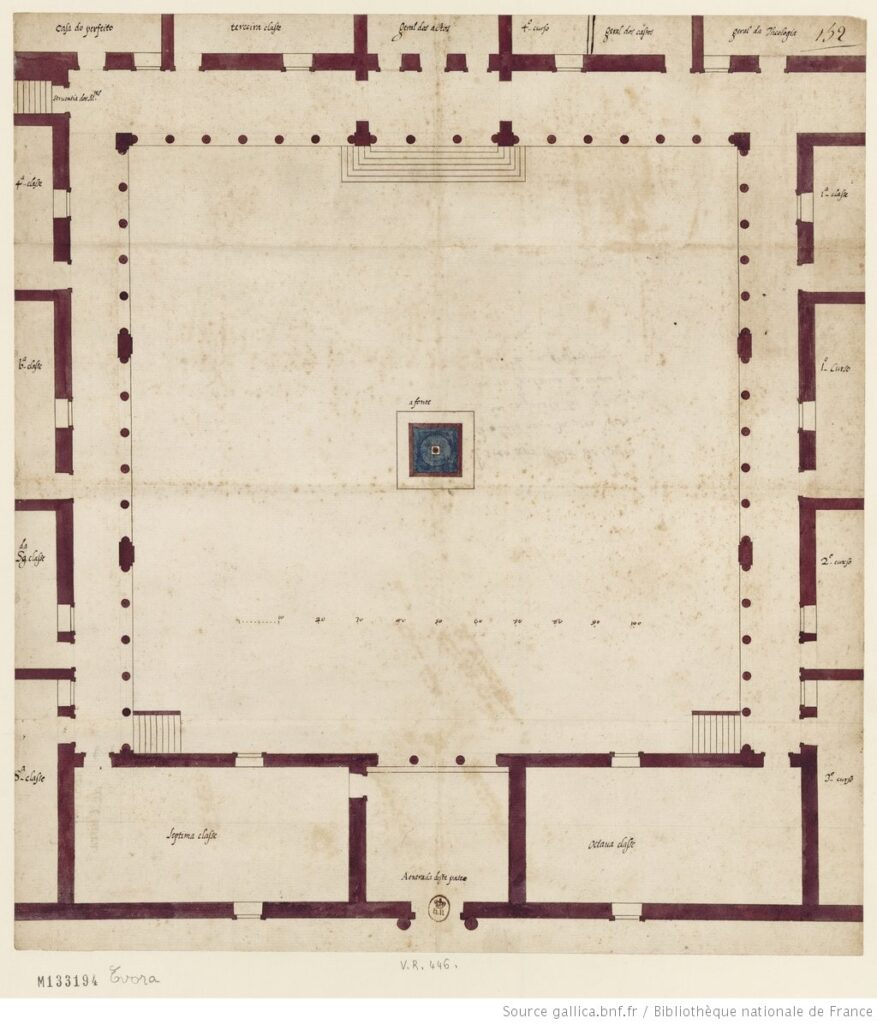

In this sense, the relationship with the University of Coimbra and with some of its buildings, that emerged in the sphere of its recent re-foundation, would have been pertinent. We were unable to identify the author of the design for the Gerais patio, the largest element of the Evorean complex, but it is very likely – a thesis we defend – that it copied the unfinished large square courtyard of the classes of the also never finished first College of Arts in Coimbra (fig.7), located in the city’s downtown, and from which, we believe, it even copied the exact dimensions (160 hand spans, about 36 meters, on each side – Lobo, 2006, 160).

Fig. 7. College of Arts I (1548-55), Coimbra, as imagined by Hoefnagel. Detail of the city view (cª. 1567) published by Georg Braun, Urbium Praecipuarum Mundi Theatrum Quintum, Cologne, 1599.

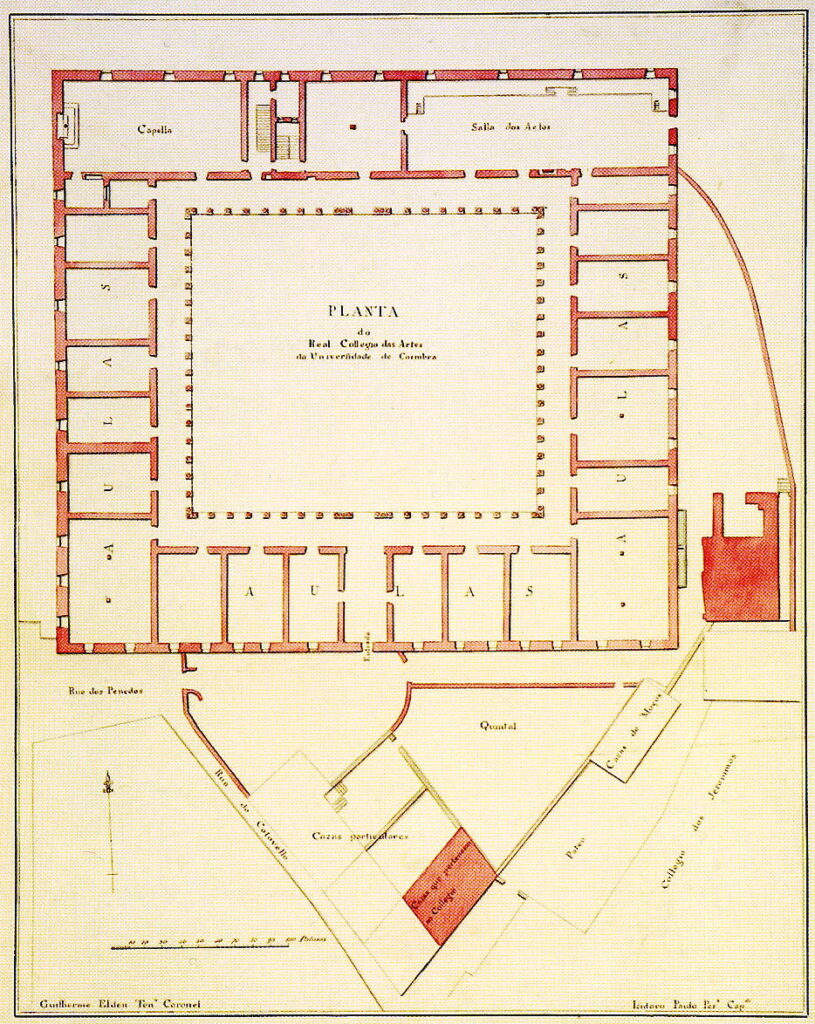

The relationship with the Jesuit complex in Coimbra is also evident. The cruciform plan of the “center” of the College of Jesus seems to have a reflection, in Évora, in the perpendicular crossing of the wings of the refectory and the infirmary. In the opposite direction, the Gerais patio of Évora (fig.8), which was older, influenced the planimetric scheme of the second College of Arts (fig.9), built by the Coimbra Jesuits, next to their main building.

Fig.8. College of Espírito Santo, Évora. Plan of the Gerais patio (erected in 1559) between 1574 e c. 1590, BnF – Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, étampe Hd-4c, 152/VR 446 (Source: BnF Gallica).

Fig. 9. College of Arts II (i.1568), Coimbra. Ground floor plan, Guilherme Elsden and Isidoro Paulo Pereira, cª.1772, Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra, Ms.3377/62.

In Coimbra, and because of the “portionist” students, inherited from the secular College of Arts in downtown, the program (a Jesuit college plus a classroom courtyard) was divided into two large buildings (the Colleges of Jesus and Arts II, fig.10), a requirement which in Évora was merged into a single structure. In this sense, the College-University of Espírito Santo (fig.11) is a kind of typological hybrid, aggregating in its configuration two, in our view, separable architectural models – a first model essay of a Jesuit College (that of Coimbra) and an “Arts College” (the courtyard of the Gerais).

Fig.10. College of Jesus and College of Arts II, Coimbra. Drawing by Carlo Grandi, 1732, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Lisbon, E 926 A.

Fig.11. College-University of Espirito Santo of Évora. Aerial photograph, by Manuel Ribeiro.

Bibliography

Manuscript Sources:

- Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Cod. 8842.

- FIALHO, Manuel (w/d, first quarter of the 18th century): Évora Illustrada, Biblioteca Pública de Évora, Tome 3, Cod. CXXX/1-10.

Printed Sources:

- Castelo Branco, Fernando (1959): “As origens da Universidade de Évora”, A Cidade de Évora, Évora, Year XVI, nºs 41-42, p.37-46.

- Espanca, Túlio (1948): “Alguns Artistas de Évora nos séculos XVI-XVII”, A Cidade de Évora, Évora, Year VI, nº15-16, p.131-287.

- Espanca, Túlio (1959): “Notícia dos edifícios do Colégio e Universidade do Espírito Santo de Évora”, A Cidade de Évora, Évora, Year XVI, nºs 41-42, p.155-185.

- Espanca, Túlio (1966): Inventário Artístico de Portugal, tomo VII – Concelho de Évora (2 vols.), Lisboa, Academia Nacional de Belas-Artes, 1966, Vol. I, p.71-91.

- Fonseca, Francisco da (1728): Évora Gloriosa, Roma, Officina Komarekiana.

- Franco, António (1714): Imagem da Virtude em o Noviciado da Companhia de Jesus do Real Collegio do Espírito Santo de Évora, Lisbon, Officina Real Deslandesiana.

- Franco, António (1728/1945): Évora Ilustrada, publicação, prefácio e índices de Armando de Gusmão, Edições Nazareth, Évora.

- Lavajo, Joaquim (1991): “Os Jesuítas e as Missões no Alentejo no Século XVI”, Boletim Igreja Eborense, Évora, nº15, p.27-50.

- Lima, Manuel C. Baptista (1947): “Um filho de D. Pedro II na Universidade de Évora”, A Cidade de Évora, Évora, AnoV, nº12, p.165-182.

- Lobo, Rui (1999), Os Colégios de Jesus das Artes e de S. Jerónimo, Coimbra, Edarq.

- Lobo, Rui (2006): Santa Cruz e a Rua da Sofia. Arquitectura e urbanismo no século XVI, Coimbra, Edarq.

- Lobo, Rui (2009): O Colégio-Universidade do Espírito Santo de Évora, Évora, CHAIA-Universidade de Évora.

- Lobo, Rui (2012): Fica este grande pateo tam apparatoso à vista. O Colégio-Universidade do Espírito Santo de Évora, in Sara Marques Pereira and Francisco Lourenço Vaz (Coord.), Universidade de Évora (1559-2009). 450 Anos de Modernidade Educativa, Lisbon, Chiado Editora, 2012, pp.473-488.

- Martins, Fausto Sanches (1994): A Arquitectura dos primeiros colégios jesuítas em Portugal, 1542-1579, PhD Thesis, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Oporto, author’s print.

- Pereira, Paulo (1992), “A Arquitectura Jesuíta. Primeiras fundações”, Oceanos, nº12, CNCDP, Lisbon, p.104-111.

- Polónia, Amélia (2005): D. Henrique. O Cardeal-Rei, Lisbon, Círculo de Leitores.

- Rodrigues, Francisco (1931-50): História da Companhia de Jesus na Assistência de Portugal, 4 Vols, Oporto, Apostolado da Imprensa.

- Sanchez Rivero, Ángel e Mariutti de Sanchez Rivero, Angela (edition and notes, w/d): Viaje de Cosme de Médicis por España e Portugal (1665-1669), Madrid, Sucessores de Ribadeneyra.

- Santos, Paulo F. (1963): “Contribuição ao estudo da arquitectura da Companhia de Jesus em Portugal e no Brasil”, Actas do V Colóquio Internacional de Estudos Luso-Brasileiras, Coimbra, p.515-569.

- Teles, Baltasar (1645-47): Chronica da Companhia de Iesu na Província de Portugal, 2 Vols., Lisbon, Paulo Craesbeeck.

- Veloso, José Maria de Queirós (1949): A Universidade de Évora. Elementos para a sua História, Lisbon, Academia Portuguesa da História.